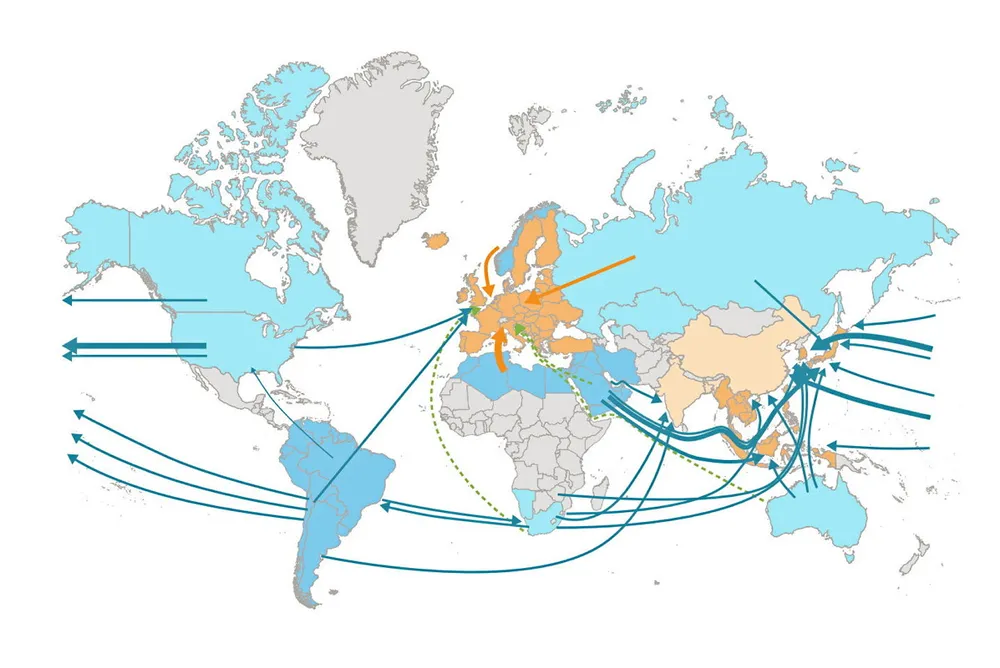

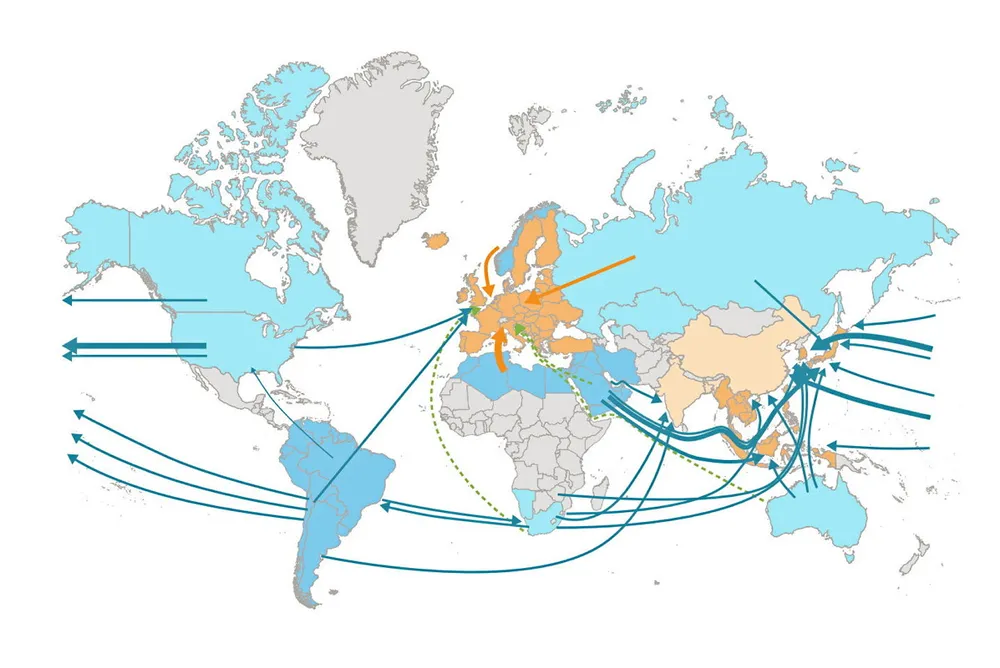

More than 60% of all clean hydrogen will be transported over long distances by 2050: Hydrogen Council

Pure H2 will be traded via pipeline, with derivatives such as ammonia moving by ship, says new report

Pure H2 will be traded via pipeline, with derivatives such as ammonia moving by ship, says new report