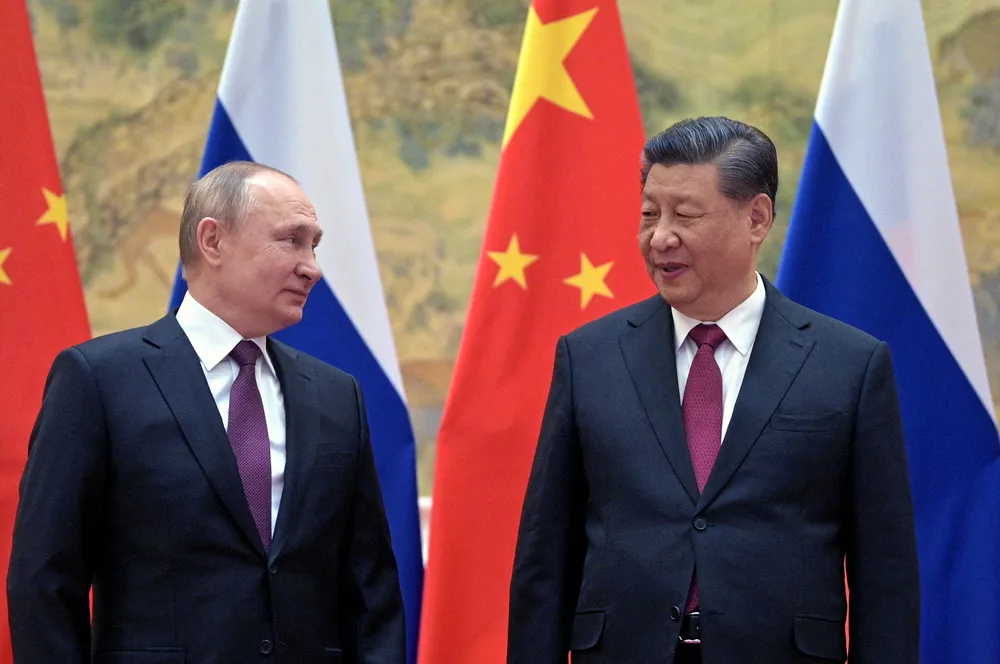

ANALYSIS | Russia scraps blue hydrogen export plans following Ukraine invasion, with no chance of re-routing to China

The sanctioned country is set to slash planned H2 production by almost 75%, but gas contracts being negotiated with Beijing could prompt China to shift from black to grey hydrogen