'Domestic heating demand can support new $1.6bn blue hydrogen project — and justify more fossil gas extraction,' says UK regulator

North Sea Transition Authority pitches business case to redevelop Bacton gas terminal as blue H2 project, with ‘overarching goal’ of repurposing existing infrastructure

Hydrogen: hype, hope and the hard truths around its role in the energy transition

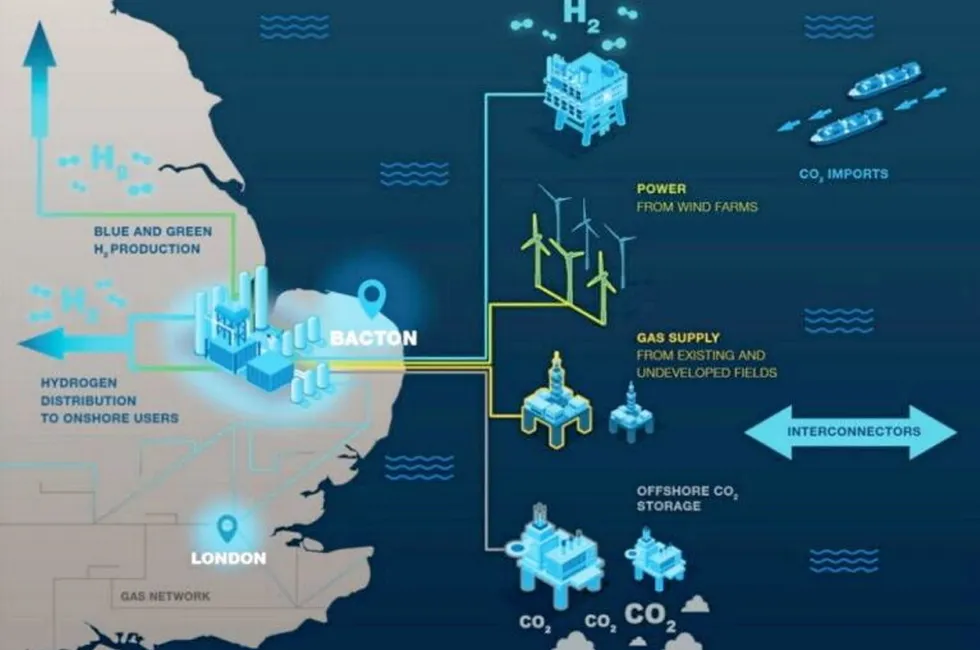

The proposed Bacton Energy Hub (BEH) concept, currently being promoted for development by offshore regulator North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) — known as the Oil & Gas Authority until March this year — envisages a new blue hydrogen production site in north Norfolk on the site of the Shell- and Perenco-owned Bacton gas terminal, which currently processes around a third of all the UK’s gas supplies.

The regulator, which is also responsible for managing the UK's oil and gas licensing, wants a consortium to form and come forward to develop the project.

The UK government is set to decide on whether it will support hydrogen heating and blending in 2026, several months after the Q3 2025 final investment decision (FID) NTSA says would be necessary to get the project on line by 2030.

One key benefit of the scheme is that it could allow hydrogen production to begin early, the regulator said, but it noted that the overarching goal of the Bacton project would be to “harness the potential of repurposing infrastructure”, such as the Bacton terminal and the gas pipelines networked around it.

But perhaps most signficantly, the Bacton Energy Hub would enable the development of as-yet-untapped fossil gas reserves in the area.

“A CCS-enabled hydrogen plant can potentially facilitate the development of previously undeveloped off-spec natural gas, increasing the accessible gas reserves to produce hydrogen in the UK to meet energy security needs,” said the NSTA. “Together with the recently launched 33rd licensing round, this opens a new opportunity for development of this type of resource in a manner aligned with net-zero objectives.”

Specifically, the report identifies 2 trillion cubic feet (around the equivalent gas consumption of a medium-sized economy such as Turkey) of untapped North Sea reserves which could supply the Hub.

A CCS programme could capture a significant portion of carbon emissions from the fossil gas — although a successful programme is yet to be pioneered — but it would not abate methane emissions from upstream extraction or blue hydrogen production. Methane is 84 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide over 20 years.

NTSA estimates that the smallest iteration of the Bacton Energy Hub project would require equivalent to around 310 million cubic feet a year, while the largest iteration would need to be supplied with extra gas imports from 2040.